IED's Space Program for Autumn 2013 has looked at the cellular network in general, the use of mobile devices and technologies within exhibitions and museums, collaboration and interactivity, and research methods. I want to focus on a few main themes that have come from the projects, conferences and research that have been a part of this: Mobile device usage in museums, the changing state of museum collections, and the audience's expectation of museums/the museum's purpose.

This is not intended as a comprehensive, or necessarily cohesive exploration of the issues discussed - more an overview and loose outline of some initial thoughts, but I will then bring it into a loose conclusion around the role and impact of digital technologies and experiences on museums and their artefacts.

Mobile Devices and Museum Content

In 'Designing for Mobile Visitor Engagement', Sherry Hsi discusses her work with mobile technologies as part of the Exploratorium in San Francisco, outlining a number of insights from the early days of the technology (1997) to more up to date experiments (2007). The key takeaway seems to be the need for the technology to work seamlessly with the spatial experience, allowing it to highlight elements of the exhibits for the users:

Multimedia content can be designed to be compelling enough to provoke users to try new things with exhibits, even in a setting that competes for social and physical attention.

The example given shows a visitor placing their head into an exhibit called the 'Echo Tube' with the caption "Try shouting with your head inside the tube". The friendly tone and use of an illustrative image serves to encourage the visitor to try and this is particularly important around interactive or technological exhibits, the viewer may not feel comfortable or be used to participating within museum exhibits and a reassuring enticement can help them overcome that discomfort.

Hsi discusses ways that they added deeper content to the multimedia guides they were creating but states that:

When asked about extending their experience, most visitors liked the idea of in-depth content and activities being available to them but said they would prefer to access such resources after a visit on the Internet.

This relates to my findings in the Atmosphere Gallery in the Science Museum, from observing visitors with the different forms of exhibits I saw that, while visitors would engage for varying amounts of time with the more playful, immersive or interactive exhibits, there was little to no engagement with the 'Deep Content' screens. These were portrait touch screens, often placed by seats, with text and video content displayed in editorial layouts reminiscent of web pages.

This relates to my findings in the Atmosphere Gallery in the Science Museum, from observing visitors with the different forms of exhibits I saw that, while visitors would engage for varying amounts of time with the more playful, immersive or interactive exhibits, there was little to no engagement with the 'Deep Content' screens. These were portrait touch screens, often placed by seats, with text and video content displayed in editorial layouts reminiscent of web pages.

When the visitor often has a touchscreen, web enabled mobile device on their person at all times, these types of screen offer very little extra for the outlay of learning a new interface and hunting for content.

This is not to say that media and information in museums can be taken care of entirely by the user's devices. At NODEM 2013 in Stockholm, Allegra Burnette from the Museum of Modern Art in New York discussed the museum's strategy and process for their new audio guides. They performed research showing that, while 74% of visitors had a mobile device, and 59% of those had an iPhone, ( the audio was web accessible ) the audio guides were still widely picked up and used. Two reasons were offered for this: They are easier to just pick up and use and visitors didn't want to have to recharge the battery on their device.

Burnette explained, however, that MoMA used Apple's iOS (via iPod touches) as the underlying system for the new guides, due to users familiarity and the fact that the software could then be distributed to users own devices. In her essay, Hsi mentions that a takeaway from the Exploratorium work was that

Designing personalization in technology can be a powerful lure. People are inherently interested in themselves and discovering something interesting about themselves. Personal media created by a visitor can act as a lure, to both try a physical exhibit and check out media after heading home.

The MoMA guides take advantage of this, offering a photo taking and sharing functionality that has had up to 20,000 photos taken per day and 'MyPath', which offers the visitor the ability to track, and later access, their journey through the museum and tagged information and content. This, Burnette says, allows for an "Experience across devices & across physical boundaries."

This changing of boundaries and the museum experience is something I want to look at in the next section.

The Visitor's Expectations and the Museum's Purpose

At NODEM 2013 in Stockholm, Kimmo Artila presented some facts from the Finnish Museum association, relating to the changing expectations that visitors have of museums. In 2001 a survey showed that visitors expected Information, Entertainment and Experience (in that order) from museums, with Information taking up the majority (70%) of expectation. The same survey in 2011 showed the breakdown as Experience (31%), Information (25%) and Entertainment (21%).

In line with this change, Gerfried Stocker, Artistic Director of Ars Electronica, discussed the aims and methods of the Ars Electronica Center, he outlined their "Interactivity First" method of engaging and including visitors in the exhibitions and with the objects and the fact that the collection exists to stimulate communication, collaboration and interchange between areas of society.

One of the methods through which they achieve this is the Laboratory - a space to run participatory workshops as part of exhibitions, specifically provided with space within these exhibitions so they could be 'pop up' in style, lowering the barrier to participation as the visitors do not have to move to a separate area of the museum to be involved.

Richard Sandell, also speaking at NODEM, discussed the controversy over the censorship of 'A Fire in My Belly' at the Smithsonian and some of the negative media coverage of shout, an LGBT exhibition in Glasgow placing museum encounters in a changing mediascape. The museum's message was presented as being fluid, changeable by the actions and opinions of the visitors, and also by the media and activists reporting and commenting on the exhibitions.

Engagement, comment and collaboration can help museums become less didactic. We need to reconcile the museum's ability to shape the world with the richness of debate and sharing.

The museum can be a place to present ideas and perspectives, but also to explore and shape them in collaboration with the visitors and the societal context and themes around the museum, its exhibitions and artefacts.

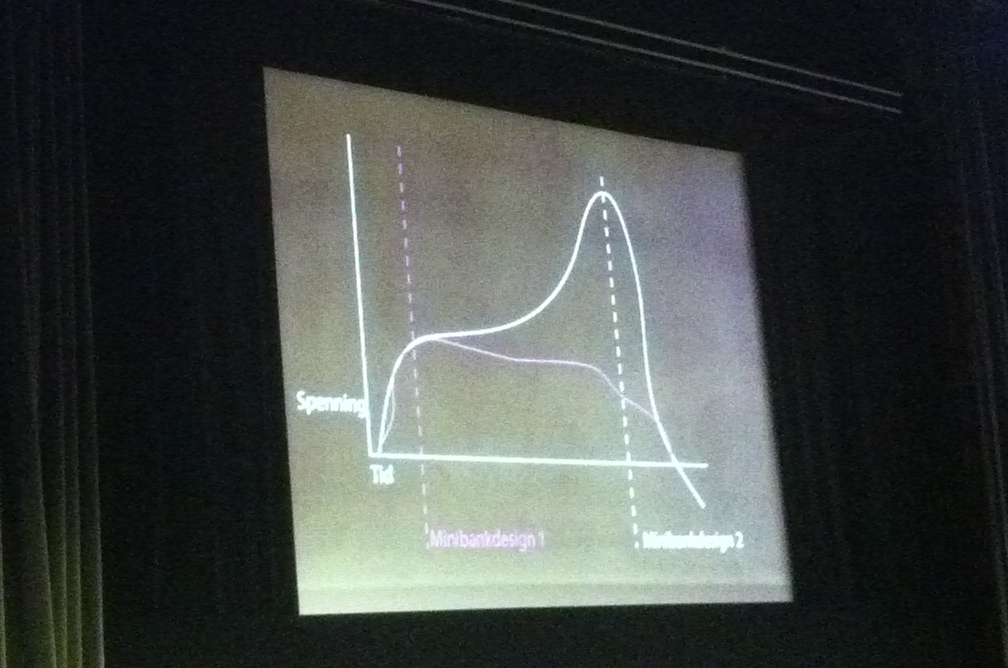

A technique for this was put forward by Nils Wiberg in his talk 'Dramaturgy in Interaction', he suggested that the exhibition or exhibit should provide a thread or narrative, but not "force visitors to follow it, offer it up optionally". Using the interaction we have with cash machines and its reflection of the classic structure of drama he outlined the structure of an experience at the Norwegian Seabird Center:

A technique for this was put forward by Nils Wiberg in his talk 'Dramaturgy in Interaction', he suggested that the exhibition or exhibit should provide a thread or narrative, but not "force visitors to follow it, offer it up optionally". Using the interaction we have with cash machines and its reflection of the classic structure of drama he outlined the structure of an experience at the Norwegian Seabird Center:

- identify hero

- contextualise story

- identify threat

- climactic drama

- contextualise

- resolution

Here, using an avatar to get people involved, the experience creates empathy with the seabird and a deeper, more meaningful experience as part of the museum.

So, the visitor to a museum expects a fuller experience, and museums are open to that provision. When they operate in a more didactic manner, undertaking censorship, visitors and activists can provide counter arguments both through widely accessible digital media/publishing and spatial interventions in or near the museum. This changes the nature of curation and presentation of the collections or experiences within the museum. The artefacts are more than just objects, and are exhibited in more ways than just the space of the museum.

Museums as a collection of information

Museums are no longer just collecting objects, they are collecting information. This has changed their attitude to permanent collections. They need now to take into account databases and collection management systems.

Kimmo Artila

The museum collection has changed, the museum artefact has changed, the museum has changed. In 'Entering the Flow: Museum between Archive and Gesamtkunstwerk?', Boris Groys discusses the museum in relation to the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art. He frames the change as the difference between an exhibition and a curatorial project.

The curatorial project ... is then the Gesamtkunstwerk because it instrumentalizes all the exhibited artworks and makes them serve a common purpose that is formulated by the curator. At the same time, a curatorial or artistic installation is able to include all kinds of objects: time-based artworks or processes, everyday objects, documents, texts, and so forth. All these elements, as well as the architecture of the space, sound, or light, lose their respective autonomy and begin to serve the creation of a whole in which visitors and spectators are also included.

This foregrounds the work of the curator in combining the aspects of a museum, but doesn't take into account the impact of digital technologies that Antila mentions. The Design with Heritage event at the V&A, however, covered this in a number of ways.

Firstly, during the round table discussion, the idea of 'authenticity' was discussed in relation to the digital. Authenticity through physical objects was outlined as an important part of the museum's purpose, as Gareth Williams said in his talk "museums are repositories of physical things that embody knowledge" and posited that digital replicas were a "challenge to the museum's authority and authenticity". Williams then went on to discuss restoration and replicas, bringing up the full scale, identical replica being built of Tutankhamun's tomb, to preserve the original asking "is the degenerated original more authentic than the original?".

It's an interesting question, and relates to the limits of physical space as well as the fragility of artefacts. The Mechanical Curator project from the British Library goes some way towards looking at what happens when artefacts (in this case, books) are digitised and then distributed without a strong curatorial stance or even necessarily an order. Discussing the project at NODEM, Nora McGregor said that the project offered a new way of "viewing our collections as data, access at scale is breathing new life into collections and is inspiring for curation". She offered a quote by Franco Moretti:

Reading individual works is as irrelevant as describing the architecture of a building from a single brick, or the layout of a city from a single church

This scale of access and distribution echoes the affect that digital/network technologies have had on other areas of culture (such as music) and offers up a fresh challenge for museums. Williams, however, offers a positive conclusion:

Digitalism will not supercede the authentic object, it will be to its benefit.

Jussi Ängeslevä (ART+COM) discussed the 'Aura of the Digital' at Design with Heritage, offering insight into the use of digital technologies in museum and exhibition contexts, as well as the importance of technology being "part of the communication, part of the story" rather than something used to appear contemporary or cutting edge. In line with this, Ängeslevä discussed an ART+COM project called 'River Is', produced for a pavilion in Gwangju, South Korea, which encodes a computationally designed experience in a 3d milled mirror sculpture. Using a light, visitors can discover the encoded information.

Jussi Ängeslevä (ART+COM) discussed the 'Aura of the Digital' at Design with Heritage, offering insight into the use of digital technologies in museum and exhibition contexts, as well as the importance of technology being "part of the communication, part of the story" rather than something used to appear contemporary or cutting edge. In line with this, Ängeslevä discussed an ART+COM project called 'River Is', produced for a pavilion in Gwangju, South Korea, which encodes a computationally designed experience in a 3d milled mirror sculpture. Using a light, visitors can discover the encoded information.

This is an experience that's incredibly specific to the particular pavilion/context in which it is installed. It can only exist in that particular form in the precise location it is in, otherwise it would not function. Through this specificity this unusually (for a digital object/experience at least) bespoke object gains an authenticity of its own. As Williams puts it, it has an "Experiential Authenticity".

This experiential authenticity seems to be the aim for a lot of the digital content within museums, and logically so. As Ängeslevä mentions, "if it's a screen and keyboard, then you might as well be at home" - the internet is a fantastic platform for deep content, linked and referenced, artefact placed in relationship to other artefacts through databases and hyperlinks but it's not so immersive. The ability to be physically present in a museum with others and to share experiences is incredibly important for learning and enjoyment. The museum as a collection of information (be it research, embodied in artefacts or displayed in text) still stands but, perhaps, the main aim of the physical side of a museum (in conjunction with digital technologies) is as a creator of experiences, as a platform for discovery. The museum is no longer fixed in one place, it can distribute and collect information globally through the internet and offer learning opportunities as a result of that, perhaps the importance of the museum as a physical space is that it allows human connections to reinforce learning and can offer specialised, specific and spectacular experiences that the visitor cannot have at home.